Showy orange and silver gulf fritillary butterflies will love your garden if you grow their favorite native nectar and host plants.

* All photos on this page were taken by me unless otherwise noted. Please provide content and photo credits to thesouthernwildgarden.com.

Why gulf fritillaries?

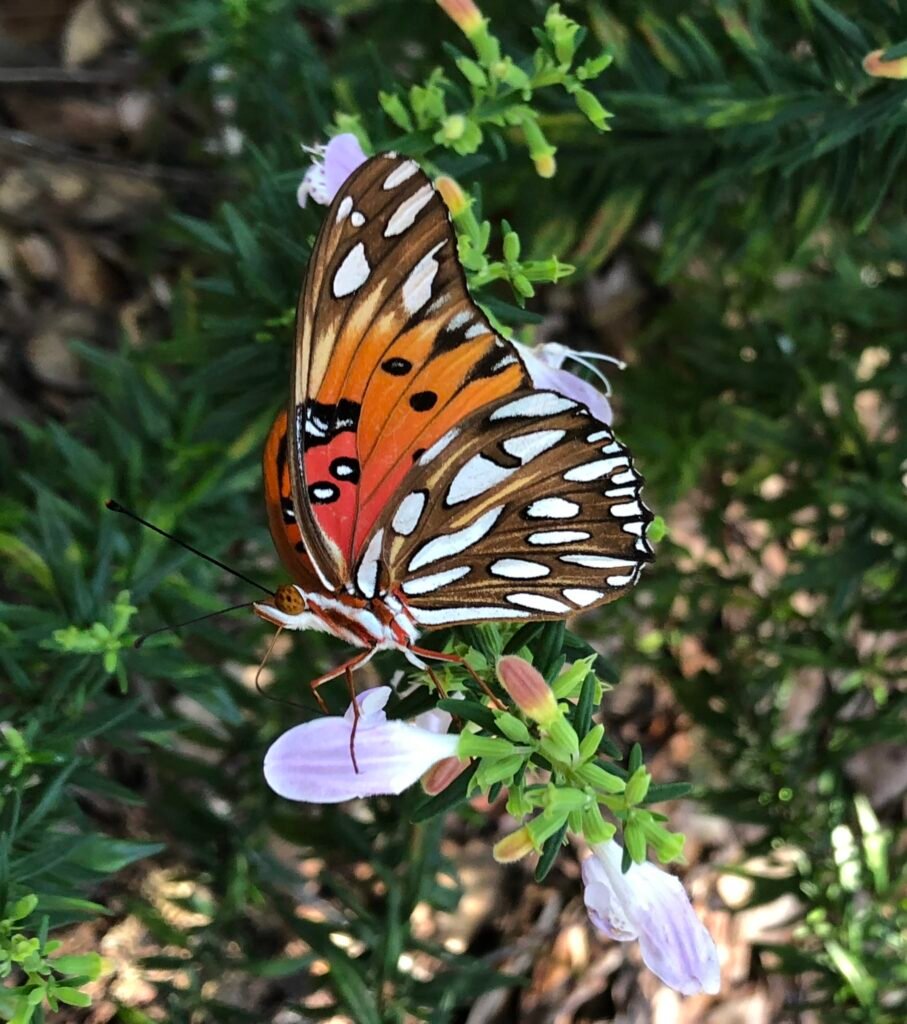

In the southeast, gulf fritillary butterflies are the “other” migratory orange butterfly. While smaller than monarch butterflies, gulf fritillaries are arguably showier, with gorgeous silver spots decorating the underside of their wings. Drawn to almost any flower, gulf fritillaries will swarm a blooming garden, especially during fall migration. You will find their sunny orange color combined with flashes of shining silver enchanting as they greedily flutter from flower to flower looking for food.

When not stopping for nectar or to investigate a passion vine, gulf fritillary butterflies fly low and fast. During fall migration, I entertain myself by sitting on the porch and watching a kaleidoscope of fritillaries pass by on their way South.

What are gulf fritillaries?

Gulf fritillaries (Dione vanillae) are butterflies in the brush-foot Family Nymphalidae which is the largest and most diverse family of butterflies. All the members of this family look like they only have four legs because the first set of legs are very small and brush-like, hence the name. Within this family, fritillaries, along with zebra longwings and Julia, belong to the Subfamily Heliconiiae or longwing butterflies. Longwing butterflies are characterized by elongated wings, slow fluttery flight, holding their wings open when feeding on flowers or basking, and having a relatively long lifespan for a butterfly. Most of these butterflies also use passion vines as host plants, but more about that later.

Within Heliconiiae, gulf fritillary butterflies are in the Genus Dione, which is found from the southern United States to South America. The species name vanillae was given to the butterfly in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus who seems to have taken the name from an earlier painting by Maria Sibylla Merian. In the painting, a gulf fritillary adult and caterpillar are shown on a vanilla orchid. While a beautiful depiction, vanilla orchids do not seem not to have any ecological significance for fritillaries.

Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Merian is a fascinating historical figure. Her contributions to science, particularly entomology, through her study and art were of enormous significance. As a scientist myself, I can’t believe I never came across her remarkable story in my many years of post graduate education. But now, thanks to the gulf fritillary, I know that she conducted some of the earliest research on metamorphosis, the phenomenon of caterpillars turning into butterflies and moths. She led an expedition to Suriname in the early 1700’s to study and document the flowers and insects, an accomplishment that seems boundary breaking on so many levels. Her subsequent production of Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam) in 1705 was the pinnacle of an astounding career.

Description

While a number of fritillaries are found in North America, in the southeast, gulf fritillaries are distinctive as the only medium-sized bright orange butterfly with elongated silver spots on it’s underwing. The gulf fritillaries’ 3 inch wingspan is decorated with three small white spots on their forewings as well as a black chain-like border on their hindwings. The females are a duller orange with more black markings making them appear darker than males.

Gulf fritillaries are considered a “southern” fritillary thriving in warm climates, unlike “typical” fritillaries that make up most of the group and are found in the north and mountains. Gulf fritillaries inhabit the southernmost portions of the United States from southern Georgia through southern California year round. In the summer, they generally migrate north forming breeding colonies throughout the southeast and parts of the central U.S. and California. Gulf fritillaries cannot survive temperatures below 21 degrees Fahrenheit, so large numbers move south in the late Fall. Researchers have estimated that millions of gulf fritillary butterflies may move through Central Florida each autumn.

Key Attributes

| Scientific Name | Dione vanillae |

| Identification | Long bright orange wings with black markings above and elongated silver spots below |

| Distribution | Southern US through Central America, Caribbean to South America |

| Size | Wing span 2.5 – 3 inches |

| Habitat | Open areas including roadsides, parks, gardens, coastal beaches, fields |

| Flight | Year-round in Florida and Texas, migration north in warmer months |

| Host Plants | Passion vines including Passiflora lutea and P. suberosa |

| Nectar Plants | Spanish needle (Bidens alba), obedient plant (Physostegia virginiana), elephant’s foot (Elephantopus tomentosas), blue mistflower (Conoclinum coelestinum), Georgia calamint (Clinopodium georgianum) |

How to attract gulf fritillary butterflies?

If you live within the gulf fritillaries range, you’ll want to have their host plant, passion vine, as well as a variety of nectar plants in your garden. Gulf fritillaries love flowers and sunshine, so they will find an open sunny landscape with lots a of color irresistible.

Host Plants

Gulf fritillaries lay their eggs almost exclusively on their host plants in the Genus Passiflora, commonly known as passion vine or passion flower. Most of the species in this family are found in the tropics of Central and South America, but over a dozen native species of passion vine occur in North America primarily in the southern states of Florida, Texas, and Arizona. Gardeners in the southeast may find a few of these species readily for sale including purple passion flower also known as maypop (Passiflora incarnata), corkystem passion flower (Passiflora suberosa), and yellow passion flower (Passiflora lutea).

How to Grow Passion Flower

Purple and yellow passion flowers have the widest distribution of the North American Passiflora, growing in the central and eastern US as far north as Pennsylvania. Purple passion flower is fairly flexible in it’s preferred habitat conditions and will readily grow in full sun to part shade in a variety of soil types, while yellow passion flower generally likes more shade and fertile, average to moist, well drained soils. Gardeners consider both species easy to grow.

Also referred to as passion vine, these plants are a flowering vine that will happily grow up to 25 feet in length, rambling along the ground or using it’s tendrils to climbing any available structure. Purple passion flower is known to become unruly, using underground runners to send up shoots and spread as far as it is allowed, while yellow passion vine is considered better behaved in the garden. Both plants produce unique pretty flowers with wavy petals and showy stamens followed by edible fruits that wildlife finds tasty but humans not so much. I would highly recommend growing the native straight species of passion vine rather than a cultivar as some butterfly species will not use genetically modified plants as host plants.

Egg Laying and Larval Stage

Gulf fritillaries will often lay their small yellow eggs singly on leaves, stems, or tendrils of passion vines. Passion vine is an attractive host plant because the leaves contain chemical compounds which make caterpillars and adult butterflies unpalatable to predators like birds. Because passion vine is a host to numerous butterfly species including fritillaries, you will frequently find caterpillars of multiple species munching down on your passion vine throughout the growing season. In most cases, gardeners will find their passion vine completely denuded of leaves multiple times throughout the summer. At higher latitudes, passion vine naturally dies back in the winter, although yellow passion flower is a little more cold hearty than others.

Eggs will hatch into tiny yellow-orange caterpillars. Tiny caterpillars will molt and grow into orange caterpillars with brown stripes and black branched spines. Spines are harmless but the distinct coloration is a warning to predators that they, like the adults, are toxic to predators. Caterpillars will form chrysalises on their host plant or on plants or structures nearby. Fritillary caterpillars from my garden seem to prefer forming chrysalises on the cement walls of my garage rather than on their host vine. Chrysalises are a mottled brown and in the shape and color of a dead leaf, allowing caterpillars to remain camouflaged while they transform into butterflies.

Nectar Plants

Gulf fritillary butterflies are very fond of flowers and, in my observation, will try to nectar on just about any flower they encounter. While any colorful treat will attract their attention, there are a few plants that will keep them enthralled for longer.

Some of gulf fritillaries’ favorite native plants are Spanish needle (Bidens alba), obedient plant (Physostegia virginiana), elephant’s foot (Elephantopus tomentosas), blue mistflower (Conoclinum coelestinum), Georgia calamint (Clinopodium georgianum), and blanketflower (Gaillardia spp).

Spanish needle

Spanish needle, also commonly referred to as common beggartick and butterfly needle, is a member of the Aster Family. Its small white flowers are exceedingly attractive to a wide variety of pollinators. In my part of the World, gulf fritillaries’ fall migration coincides with peak blooming of Spanish needle. In October, I will find fritillaries swarming patches of the dainty white flowers to drink nectar.

Despite being adored by pollinators, Spanish needle is a difficult plant for many gardeners to love. In addition to looking “weedy” if not pruned back, Spanish needle spreads aggressively through it’s production of thousands of twin-barbed seeds that readily attach to fur and clothes to be dispersed throughout the surrounding landscape. You will have to determine whether the labor involved in deadheading and pulling seedlings to keep Spanish needle in check in your garden is worth gaining the myriad of pollinators, including gulf fritillaries, it will undoubtably attract.

While not readily available from local native nurseries, if you look along roadsides in the southeast in the Fall, you will likely find some Bidens from which to collect seeds. Seed germination rate appears to be very high. Other than not being salt tolerant, Spanish needle seems to be able to grow in almost any soil type with full to part sun.

Georgia calamint

Another fall blooming pollinator favorite, Georgia calamint, also commonly known as Georgia basil or Georgia savory, is a lovely little shrub belonging to the mint Family (Lamiaceae). Like many mints, the Georgia calamint’s tubular pink to lavender flowers are attractive to many bees and butterflies. I’ll often see multiple gulf fritillaries sharing a single plant with numerous carpenter bees and long-tailed skippers.

Georgia calamint is native to the southeast and grows up to 2 feet tall. Frequently available at native plant nurseries, Georgia calamint is happiest in well-drained sandy soils in full to part sun.

Other plants

Gulf fritillary butterflies are also attracted to some other native plants in the Aster Family (Asteraceae) including Rudbeckia spp., such as cutleaf coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata) and black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), climbing aster (Ampelaster carolinianus), and Stokes aster (Stokesia laevis).

Gulf fritillaries will happily feed on some tropical plants not native to most of the Southeastern U. S. like known butterfly magnets zinnias (Zinnia spp.) and lantana (Lantana spp.). There are species of lantana native to south Florida and Texas, but the lantana you will commonly find at nurseries will most likely be cultivars or species from Central and South America. Gardeners should do their due diligence if planting lantana to ensure they are not growing the invasive plant pest large leaf lantana, Lantana camara. Peruvian zinnia (Zinnia peruviana) is native to the southwest and has naturalized in some parts of the southeast including Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

What else is cool about gulf fritillaries?

Male gulf fritillaries have structures in their forewings that produce chemicals that are thought to be important in attracting females to mate. Males will court females by performing a wing clap display, alighting next to a female and rapidly clapping his wings together in front of the females face often catching her antennae between his wings in the process. Presumably, this behavior presents the female with chemical signals that allow her to choose the best mate.

In addition to mating, gulf fritillaries also use chemical scents to defend against predators. Both sexes have glands in their abdomens that emit an odor when disturbed that appears to be very unappealing to birds.

Where to find more information?

- Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 2003: Male specific structures on the wings of the gulf fritillary butterfly, Agraulis vanillae (Nymphalidae) by Rauser and Rutowski.

- Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 1984: Courtship behavior of the gulf fritillary, Agraulis vanillae (Nymphalidae) by Rutowski and Schaeffer.

- Ecological Entomology 1991: Butterfly migration from and to peninsular Florida by Walker.

- Scientific Reports 2021: Analysis of the optical properties of the silvery spots on the wings of the gulf fritillary, Dione vanillae by Dolinko et al.

- Environmental Entomology 2001: Butterfly migrations in Florida: Seasonal patterns and long-term changes by Walker.

- Journal of Chemical Ecology 2001: Novel chemistry of abdominal defensive glands of Nymphalidae butterfly Agraulis vanillae by Ross et al.

- Butterflies and Moths of North America: Gulf Fritillary Agraulis vanillae (Linnaeus, 1758).

- Florida Wildflower Foundation: Gulf fritillary

- WFSU Ecology Blog: Want to see the gulf fritillary life cycle? Plant passionflower! (Really nice photos on this site!)

- The Royal Collection Trust: Vanilla with Gulf Fritillary 1702-1703.

Pingback: The Southern Wild - How to Grow Obedient Plant in Your Garden

Pingback: The Southern Wild - How to Attract Zebra Longwings to Your Garden